Thanks to a Maharaja who chartered a new ship for ₹1.5 lakh and carried thousands of litres of holy water on board

Fresh water, an increasingly scarce resource, is high on the list of priorities for most tourists when they plan a journey to a distant land. Most of the time, the concern is motivated by fears of hygiene.

That wasn’t the case in 1902, when the SS Olympia docked in London, carrying on board the Maharaja of Jaipur, Sawai Madho Singh II. Accompanying him were 132 servants, a retinue of Hindu priests, and over 600 pieces of luggage. What stood out, however, was the amount of water on board — 8,000 litres, held in two enormous silver urns. The Maharaja’s disembarkment was, as a June 1902 edition of The Globe put it, “a remarkable sight”.

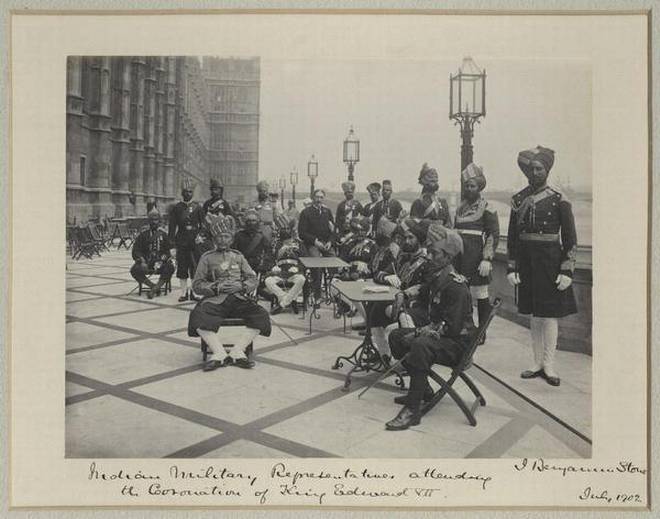

More remarkable was the provenance of the water, and the reason it had been carried more than 5,000 miles from Jaipur to London, via Bombay. Madho Singh was one of several important Indian nobles invited to attend the coronation of Edward VII after the death of Queen Victoria. Along with the Maharajas of Gwalior and Bikaner, Singh was considered loyal to the Empire, which was partly the reason behind his attendance.

The main reason, however, was to symbolise the dominion of the English Crown over its colonies by staging a grand pageantry of the Indian princes.

The adopted heir of Ram Singh II, Madho Singh, who turned Jaipur into ‘Pink City’ when Prince Albert Edward visited a few decades earlier, was a study in contrasts: his religious conservatism went hand-in-hand with the progressive policies he pursued during his reign. These resulted in the establishment of strong civic and educational systems in Jaipur.

Grand jugaad

The pressing need to attend the coronation made things difficult for Madho Singh. On the one hand, if he did not attend, it would be a breach of etiquette that could have severe ramifications. On the other, attending would mean Kala Pani (black water, or crossing the ocean) and polluting his soul as per Hindu scriptures.

Maharaja Sawai Madho Singh II. | Photo Credit: Wiki Commons

When confronted with this dilemma, Madho Singh summoned a council of religious and military advisers on what to do next and hit upon a grand jugaad. He decided to carry thousands of litres of water from the holy Ganges with him to England to prevent his soul being polluted. The water would be used for all his needs, both mundane and divine. He chartered a brand new ship for ₹1.5 lakh from travel agency Thomas Cook, and transformed one of the rooms below deck into a shrine. He also gave strict orders to the crew that no beef be consumed on board and ordered his retinue to cook all of the meals. Madho Singh also brought blacksmiths, carpenters, and other craftsmen to avoid having any work done by foreigners.

The urns themselves were enormous: 1.5 metres tall and with a circumference of 4.5 metres, each was capable of holding 4,000 litres of water. The vessels, originally three of them, had been fashioned in 1894 by melting down 14,000 silver coins, according to the Rajasthan State Archives, though what they were originally intended for is unknown. The SS Olympia set sail from Bombay; the urns and their sacred contents transported on board via a complex system of wheels and pulleys. When the ship encountered rough weather near Aden, Madho Singh, after consulting a priest on board, ordered one of the urns be tossed overboard to placate an angry lord Varuna.

The Maharaja’s arrival in England evoked both curiosity and Orientalist fantasy about Indian traditions. “The Maharajah of Jaipur’s impediments are many tons in weight, and include his gods and sacred water from the Ganges,” wrote Aberdeen Journal in 1902. The Daily News, meanwhile, prefaced its brief news report on the coronation guests with the following: “Strange, indeed, to Western ideas, are the religious observances of our Oriental visitors.”

For readers of The Sporting Times, colloquially known as the ‘The Pink ‘Un’, Madho Singh was welcome because of his city’s colour scheme. “The Maharajah of Jaipur, who has come to England with a few million gallons of Ganges water to take his monthly tub in, is a real Pink ‘Un,” said a June 1902 letter to the editor. “So true is he to the finest colour in the world, that he has every house in his capital painted a bright pink.”

The coronation, originally planned for June 1902, was postponed to August after the future king underwent an appendicitis operation.

In pomp

The ceremony included a display of troops from the Empire, as American journalist Jack London noted in his 1903 monologue about London — The People of the Abyss: “Here they come, in all the pomp and certitude of power, and still they come, these men of steel, these war lords and world harnessers. Pell-mell, peers and commoners, princes and maharajahs, Equerries to the King and Yeomen of the Guard. And here the colonials, lithe and hardy men; and here all the breeds of all the world-soldiers from Canada, Australia, New Zealand; from Bermuda, Borneo, Fiji, and the Gold Coast; from Rhodesia, Cape Colony, Natal, Sierra Leone and Gambia, Nigeria and Uganda; from Ceylon, Cyprus, Hong-Kong, Jamaica, and Wei-Hai-Wei; from Lagos, Malta, St Lucia, Singapore, Trinidad.”

One of the silver urns carried to Britain; | Photo Credit: Wiki Commons

After presenting the new king with several gifts, Madho Singh departed for home, content in the knowledge that he had satisfactorily performed his duties as a vassal and as a Hindu. “I hope by my conduct now and hereafter to my people that Rajput, even if he crosses the ocean, may yet an upright Hindoo whilst he does his duty as vassal of the English Crown (sic),” he is quoted as saying by several newspapers in 1902.

King Edward VII would die eight years later; and Madho Singh would continue to sponsor educational and welfare projects in Jaipur until his death in 1922.

As for the urns, purported to be the largest silver objects in the world, they are on display at the Diwan-i-Khas of City Palace in Jaipur. Their brother, meanwhile, is still somewhere at the bottom of the Red Sea.

The London-based journalist writes on arts and politics.